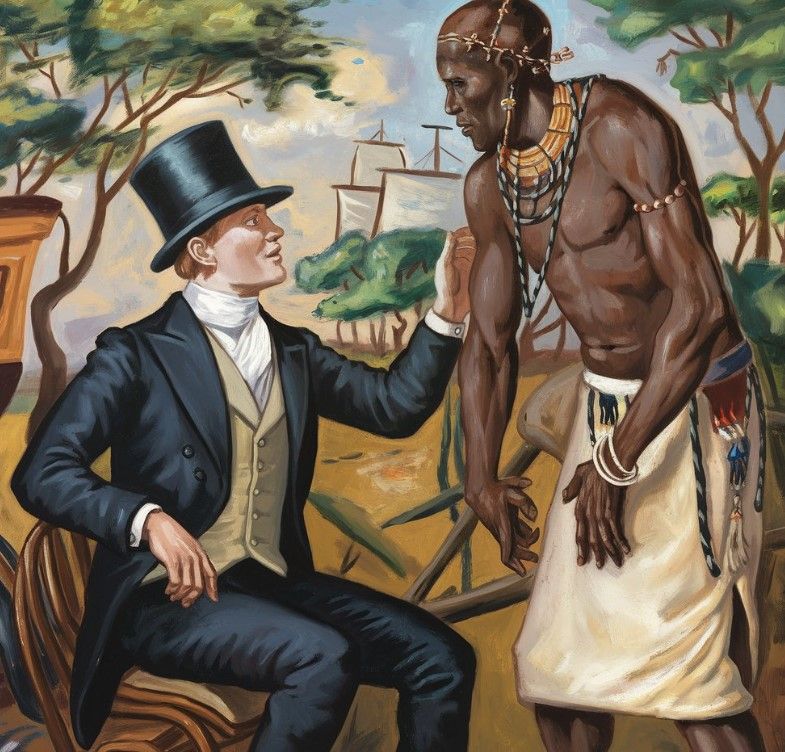

Colonialism is fundamentally about a strong group forcefully taking control of a weaker one. The arrival of colonizers is depicted as a large ship landing in a place with established ways of life. These colonizers bring guns and radically different ideas about rules, ownership, values, and the future. They immediately claim ownership of the land and begin imposing changes without collaboration. They declare sovereignty over lands that were not theirs. This reorganisation is forced, not negotiated. Colonialism reshapes relationships, social structures, and economies. The driving force behind this reshaping is the strong group’s desire for control. The power dynamic is one of dominance and submission. The distant shore has been inhabited for a long time, with people following their own customs and social structures.

Colonialism is a form of control by one group over another. Key characteristics include political control, settlement of the territory, and resource extraction. Colonizers are motivated by a belief in their own superiority and a desire to exploit resources for their benefit. Control was maintained through political dominance and exploitation, greatly impacting the colonized. Colonialism benefited colonizers through resource acquisition and power. Resistance to colonialism occurred, and long-term consequences include unequal power dynamics and economic disparities. The relationship between colonizer and colonized is characterized by exploitation and unequal power, not symmetry.

Why Empires Reached Out

European colonialism spanned hundreds of years and was not a uniform phenomenon; its goals and means varied. Driven by multiple motivations that shifted based on time, colonizing nation, and geographic location, it is crucial to understand these varied motivations to truly understand how colonial systems functioned.

A major driver of colonialism was financial gain, with the lure of potential riches proving irresistible. Early Spanish and Portuguese efforts in the Americas were motivated by the desire to find gold and silver, which boosted the European economy. Later, the focus shifted to exploiting natural resources and agricultural goods unavailable in Europe. Colonizers extracted resources like sugar, cotton, rubber, spices, and minerals from colonies in the Caribbean, Brazil, India, Egypt, Southeast Asia, and Africa. These raw materials were shipped to the colonizing country, where they were processed and sometimes sold back to the colonies or to other countries. Colonies were also forced to buy manufactured goods from the colonizing country, which provided captive markets. This helped the colonizers dispose of excess goods and stunted the colonies’ industrial development. Controlling trade routes like the Cape of Good Hope, the Straits of Malacca, and the Suez Canal was vital for efficiently transporting goods and resources. Colonialism thus affected the distribution of goods and resources while aiding the industrialization in Europe, with trade regulated to primarily benefit the colonizer.

European powers pursued colonization for geopolitical reasons, viewing it as a competitive game where gaining colonies meant rivals lost influence, thus shaping European power dynamics. Colonies enhanced a nation’s power by increasing its reputation and area of influence. Militarily, colonies offered naval bases and refueling locations, contributing to what is known as “strategic depth” – the ability to project military force and sustain operations globally. The “Scramble for Africa” exemplifies this competition, driven by the fear of other European powers gaining control of resources. Colonies represented a country’s power and importance, and colonialism was not solely motivated by economic factors; political power played an equally important role.

Ideological justifications for colonialism included the “civilizing mission” and beliefs in racial superiority. The “civilizing mission,” particularly emphasized by France and Britain, was the idea that European nations had a duty to share their culture, religion, language, government, and education with supposedly less developed people. While sometimes genuinely inspiring, it was often a false justification for exploitation. The “White Man’s Burden” exemplified policies forcing colonized peoples to adopt European ways. Ideas of racial superiority, supported by flawed scientific theories in the 1800s, portrayed non-Europeans as naturally inferior, legitimizing domination. Science played a minor role, with expeditions mapping areas and studying local populations, knowledge that helped with control. Colonizers had diverse motivations, not always genuine, ranging from greed to a desire to “civilize.” Phrenology would be an example of a pseudo-scientific theory. Scientific studies facilitated control by providing knowledge about the landscape and people that could be used for domination. These motivations were not independent; economic, geopolitical, and ideological factors combined to drive European expansion.

The Mechanisms of Control: Establishing and Maintaining Domination

Colonization began with military force, violently suppressing resistance using superior weapons and organization. Following military conquest, treaties were used to deceive local leaders into relinquishing authority. Next, colonizers imposed European-run government administrations and legal systems that favored Europeans while discriminating against the colonized.

These administrations primarily extracted resources and maintained order, not to benefit the local population. Forms of colonialism include settler colonialism (e.g., Australia, Canada) aimed to replicate the colonizing country’s society and government, and extractive colonialism (e.g., India, Congo) focused on resource exploitation. Direct rule, favored by France, sought cultural assimilation. Indirect rule, used by the British, utilized existing local leaders, proving cheaper but often destabilizing local power structures.

These forms shaped colonial experiences by affecting interaction levels, cultural impacts, and administrative interference. Railways and roads, mainly for resource export, supported colonialism. Forced labor, including slavery, was essential for colonial profitability in mines and plantations. Colonial education systems, using the colonizer’s language and curriculum, trained a subservient workforce, promoted colonial values, and suppressed indigenous knowledge. Colonial infrastructure did not improve the colony for local populaces. Colonial governments did use slavery, and negatively impacted local knowledge.

Transformation and Trauma

Colonialism had profoundly negative and lasting consequences across many areas of life. It deeply impacted colonized societies by damaging social structures, family relationships, and governments while also destroying or ignoring local leaders. Indigenous languages and cultures were weakened through the imposition of European languages, religions, and education, which created identity problems for the colonized.

Missionaries offered education and healthcare but also sought to eliminate local customs. Colonialism reoriented economies to benefit colonizers through land seizure, a shift to export crops, and the destruction of local industries. Wealth was systematically extracted, creating economic dependency. Politically, colonialism eliminated indigenous sovereignty by replacing local governments with foreign rule and arbitrarily drawing borders, causing lasting conflict.

Direct and indirect rule were implemented. It led to demographic and health crises through the introduction of European diseases, colonial policies causing famine, and forced migrations. Social and racial hierarchies were created and reinforced, with colonizers considering themselves superior and viewing colonized people as inferior, leading to feelings of worthlessness. The concept of the “Other” emerged in this context. The post-colonial nations have depended on the colonial powers as suppliers of raw materials and buyers of finished products.

Gains and Internal Shifts

Colonizing powers benefited from colonialism through economic growth, geopolitical power, and internal changes. Economically, they gained wealth through taxes on colonial trade, resource extraction by companies like the British East India Company (which significantly enriched Britain), and control of trade routes.

Colonies provided cheap raw materials (like cotton) crucial for European industrialization and served as markets for European manufactured goods, boosting the Industrial Revolution. This fueled the development of financial institutions and the growth of port cities such as Liverpool, Bristol, Bordeaux, and Lisbon. Geopolitically, colonies served as strategic assets, providing bases and resources that enhanced the global power of colonizing nations and allowed them to control key trade routes.

Colonialism influenced European culture through new ideas in art, literature, and fashion and changes in diet. Museums and world’s fairs promoted narratives of European superiority, shaping national identity. Racial theories developed to justify colonialism, influencing social issues. While wealthy individuals benefited most directly, ordinary citizens sometimes gained from employment, nationalism, or cheap goods. The text does not discuss any costs of colonialism for ordinary citizens or for the colonizing powers in general.

Resistance and the Seeds of Change

Colonial rule was never absolute; resistance was constant. This resistance took overt, violent forms like the Indian Mutiny, the Maji Maji Rebellion, the Haitian Revolution, and the Vietnamese struggle against French rule. It also manifested subtly through inaction, sabotage, and cultural preservation—protecting language, art, and traditions.

Anti-colonial resistance was characterized by diverse tactics and cultural preservation; educated elites critiqued colonizers, leading to nationalist groups advocating for independence through petitions, protests, and strikes. Both internal resistance and external factors drove decolonization. World Wars weakened European powers, exposing hypocrisy and creating external pressures for change, while the rise of the US and the Soviet Union supported anti-colonial movements, with the UN providing a platform for self-determination.

Changing ideologies within colonizing countries also contributed. Decolonization was not uniform, ranging from peaceful agreements to violent conflicts. Newly independent nations faced ongoing challenges beyond the end of colonial control, starting a new phase with various issues.

Colonialism in the Present

Colonialism, driven by greed for wealth, power, and a sense of entitlement, was implemented through military force, governance, laws, and cultural dominance, profoundly reshaping colonized societies. The destructive consequences included disrupted economies, fragmented societies, enforced political control, and lasting emotional and cultural trauma, creating lasting political instability, economic struggle, and social inequality.

The arbitrarily drawn colonial borders ignited numerous conflicts in Africa and Asia, as colonial economic policies hindered local economies and continue to be the origin of trade agreements that perpetuate neocolonialism, leading to dependence on raw material exports. Colonialism instilled social inequalities based on race, ethnicity, and class and shaped educational systems while imposing the colonizer’s language.

Neocolonialism emerged as a new form of control, with powerful nations exerting influence through financial, political, and cultural channels. While colonizers gained wealth and power, they also laid the foundation for current global inequalities, which are still unfolding today. Understanding colonialism’s legacies is critical for navigating our interconnected and unequal world and can lead to decolonization in particular regions.